|

|

The fight to certify photography as a fine art has been among the

medium's dominant philosophical preoccupations since its inception.

Photography's legitimacy as an art form was challenged by artists

and critics, who seized upon the mechanical and chemical aspects

of the photographic process as proof that photography was, at best,

a craft. Perhaps because so many painters came to rely so heavily

on the photograph as a source of imagery, they insisted that photography

could only be a handmaiden to the arts.

To prove that photography was indeed an art, photographers at first

imitated the painting of the time. Enormous popularity was achieved

by such photographers as O. J. Rejlander and Henry Peach Robinson,

who created sentimental genre scenes by printing from multiple negatives.

Julia Margaret Cameron blurred her images to achieve a painterly

softness of line, creating a series of remarkably powerful soft-focus

portraits of her celebrated friends.

In opposition to the painterly aesthetic in photography was P.

H. Emerson and other early advocates of what has since become known

as “straight” photography. According to this approach

the photographic image should not be tampered with or subjected

to handwork or other affectations lest it lose its integrity. Emerson

proposed this philosophy in his controversial and influential book,

Naturalistic Photography (1889). Appropriately, Emerson was the

first to recognize the importance of the work of Alfred Stieglitz,

who battled for photography's place among the arts during the first

part of the 20th cent.

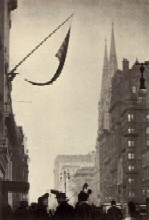

In revolt against the entrenched imitation of genre painting known

as “salon” photography, Stieglitz founded a movement which

he called the Photo-Secession, related to the radical secession

movements in painting. He initiated publication of a magazine, Camera

Work (1903–17), which was a forum for the Photo-Secession and

for enlightened opinion and critical thought in all the arts. It

remains the most sumptuously and meticulously produced photographic

quarterly in the history of the medium. In New York City, Stieglitz

opened three galleries, the first (1908–17) called “291”

(from its address at 291 Fifth Ave.), then the Intimate Gallery

(1925–30), and An American Place (1930–46), where photographic

work was hung beside contemporary, often controversial, work in

other media.

Stieglitz's own photographs and those of several other Photo-Secessionists,

Edward Steichen, one of his early protégés; Frederick

Evans, the British architectural photographer; and the portraitist

Alvin L. Coburn, adhered with relative strictness to a “straight”

aesthetic. The quality of their works, despite a pervasive self-consciousness,

was consistently of the highest craftsmanship. Stieglitz's overriding

concern with the concept “art for art's sake” kept him,

and the audience he built for the medium, from an appreciation of

an equally important branch of photography: the documentary.

The power of the photograph as record was demonstrated in the 19th

cent., as when William H. Jackson's photographs of the Yellowstone

area persuaded the U.S. Congress to set that territory aside as

a national park. In the early 20th cent. photographers and journalists

were beginning to use the medium to inform the public on crucial

issues in order to generate social change.

Taking as their precedents the work of such men as Jackson and

reporter Jacob Riis (whose photographs of New York City slums resulted

in much-needed legislation), documentarians like Lewis Hine and

James Van DerZee began to build a photographic tradition whose central

concerns had little to do with the concept of art. The photojournalist

sought to build, strengthen, or change public opinion by means of

novel, often shocking images. The finished form of the documentary

image was the inexpensive multiple, the magazine or newspaper reproduction.

For a time the two traditions, art photography and documentary photography,

appeared to be merged within the work of one man, Paul Strand. Strand's

works combined a documentary concern with a lean, modernist vision

related to the avant-garde art of Europe.

|